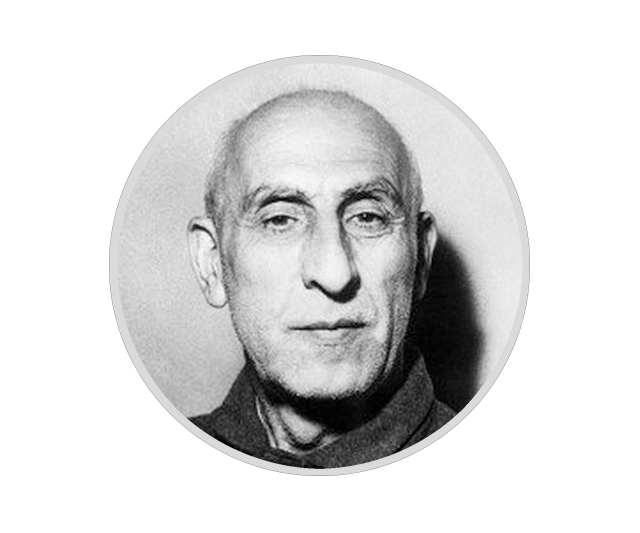

Is Erdogan overreacting? Not two weeks ago, on July 15th, the Turkish army tried to overthrow the government of Turkey in a coup attempt that ultimately failed. In the aftermath of the coup, Erdogan executed a vast purge of government employees. The number of people that have been affected by this purge is estimated to be in the tens of thousands. To see whether Erdogan is overreacting it is helpful to consider the example of another coup that also had failed but then miraculously sprang back to life: the coup against Iran’s prime minister Mohammed Mossadegh on August 15th, 1953.

The international mood was not in favor of Mossadegh. America had elected Dwight Eisenhower, the Dulles brothers were heading the CIA and the foreign ministry. Joe McCarthy was hunting for communist in all parts of the American life. This was the height of the cold war. Preventing the Soviet Union from increasing its influence was the top foreign policy priority. In the US, Mossadegh was seen as weak in the face of Iran’s communist opposition, the Tudeh. The British played to this communist angst. Their problem with the Mossadegh government had arisen when he had nationalized Iran’s oil industry. The secure supply of oil was a national security concern for the British ever since Churchill had switched the Royal Navy from coal to oil. Iran was both a source of oil and a source of considerable income. Mossadegh was messing with this comfortable status quo. The Americans and the British decided to topple Mossadegh’s government in a joint CIA-MI6 operation.

The organisation of the coup in Iran was up to the CIA agent Kermit „Kim“ Roosevelt, the grandson of the former president. When not playing tennis or enjoying a bottle of whiskey next to the pool he worked on building a network of Iranians that could be relied on to carry out the coup. The person to lead the coup and ultimately replace Mossadegh as prime minister was General Faziollah Zahedi. It was hoped that his connections inside the army would ensure the coup’s success. The shah required a lot of persuasion to sign on to the plot. When, on August 13th, he finally did, the coup could start in ernest.

The coup itself was a short and painless affair; the foreign minister had a genuinely rough evening. His house was ransacked and his wife was assaulted. Mossadegh himself had a rather more pleasant experience. When Colonel Nematullah Nassiri of the royal guard came to arrest him, it was the Colonel who was arrested instead. The coup seemed to be over before it really began.

When the shah realized that the coup had failed he fled the country. He took a plane to Baghdad and then traveled on to Rome. The shah had abandoned Iran. Mossadegh was in control. The CIA had achieved exactly the opposite of what it set out to do.

And what did Mossadegh do? Instead of moving forcefully against the putschists he held numerous meetings and went back to his preferred place to conduct the business of the prime minister: his bed.

The calm betrayed the currents stirring under the surface. The British and American agents were still plotting. The Tudeh had plans of their own and their actions created an atmosphere of chaos and fear. An odd coalition of thugs and prostitutes (really: prostitutes) used the power vacuum to mount a credible threat to the government by marching on the palace.

It was in his bed, in his grey pyjamas, that the reality of a revived coup caught him. This time, though, he was unprepared and, on August 19th, this second coup succeeded.

It is worthwhile to pause for a moment and consider the terrible prize the Iranian people and the world would have to pay because of this coup.

After the lucky outcome, the CIA thought it had discovered a ready path to influencing governments the world over. If the government of a particular country was not to its liking, all it has to do was to take some money, establish some contacts, and orchestrate a coup. It proceeded to apply this recipe in numerous countries all over the world; the results were often disastrous. Either, because the coup failed outright, or because it brought governments to power that devastated their countries. The perception of a successful coup in Iran laid the ground for one of the sadder chapters of the cold war.

The prize the Iranian people had to pay was enormous. First they had to live through the reign of the shah. His mismanagement of Iran and its economy in particular was the prerequisite for the Iranian revolution in 1979. What at first felt like ridding Iran of a hated monarch and the arrival of freedom soon turned into a nasty theocracy. Many freedoms were lost and they have not been restored to this day. To this, one has to add the ten year war against Iraq that saw the death of almost one million Iranians. Many Iranians died in gas attacks that were organized with the support of American intelligence.

In hindsight it is hard not to feel anger at Mossadegh. All he had to do, was act forcefully and jail a large number of the putschists. Because the situation was unclear, while the coup was in progress, he had to err on the side of jailing too many rather than jailing too few, to show that he was in control. The police and the army should have been in the streets and no assembly of thugs should have been allowed to gather, let alone march on the palace. The radio station should have been under special protection. In short: Mossadegh should have acted more like Erdogan is acting now.

Why, then, does the coup in Turkey leave a bad aftertaste? The democratically elected government won after all. It leaves a bad taste, because there is a chance that what we are witnessing now, is the death of a republic. Whatever form a republic takes, it should pass two tests. It should be possible to stand in the middle of a town square and criticize the government and there must be a finite tenure to the head of state. When his time is up, he should leave. Erdogan’s Turkey has failed both of these tests. Journalists and citizens who have criticized Erdogan have faced harsh consequences. Opposition newspapers were shut down, journalists have lost their jobs or faced imprisonment. Moreover, Erdogan has followed Putin’s lead and took the powers of the prime minister with him, when he became Turkey’s president. None of this bodes well for the future of the democracy in Turkey.

Here is to hoping that I am misreading these signs and that, in a few years, we see a strong Turkey with a vibrant democracy that is at peace with its neighbors and a former president that is held in high regard because he steered Turkey through rough waters and brought this Turkey about.